Yes, the headline is true, according to Car and Driver and first reported by Automotive News. Over 400 dealers are considering this move or have done it already. Don’t panic, as of February 2011, Chevrolet had 3,084 dealers, so even 400 of those would amount to 13% or about 1/8th of existing dealers. Chevrolet has said the dealers opting out represented less than 1% of Volt sales, or 288 Volts across 400+ dealerships. On average, that would mean each dealer sold less about 3/4 of one Volt, over the last two years.

Why would any dealer drop the Consumer Report’s winner of the customer satisfaction survey two years in a row? It seems that the cost of tools required to be a Volt certified dealership are driving some away from the Volt. Chevy raised requirements, which raised the cost of tools from $2800 to $5100. One of the tools is a unit that depowers the Volt’s battery so that the dealership can ship only faulty components of a battery pack, instead of the entire pack. Dealers who had only sold a handful of the extended range electric hybrid cars felt this increase in tooling costs would cut too deeply into their profit margins or even push them into a loss situation on the Volt.

Consider a small, rural dealership that sold five Volts since its launch. That’s up to $1020 of tools per Volt sold. Their clientele may also have much farther to drive than what is attainable with electricity and are opting for other fuel-efficient vehicles that don’t plug in to an outlet. At the end of November, the total number of Volts sold in the U.S. and Canada was 28,825. If every dealer sold the same number of Volts, they would have each sold nine Volts over the last two years, or just 4-1/2 per year. Of course, the old bell curve tells us that not all dealers have sold the same number of Volts. Some may have signed up for the program but only managed to sell one or possibly none. To them, that tooling cost, which was added onto previous tooling requirements, would be cost-prohibitive.

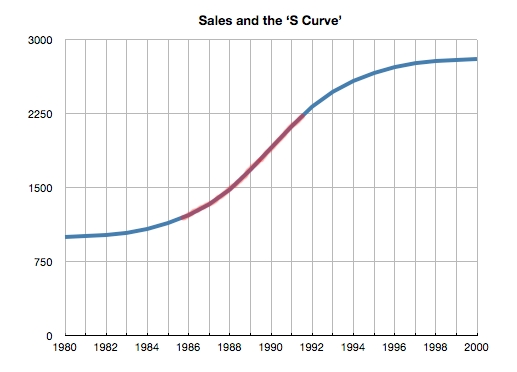

I guess I can understand their move, but unless geography and clientele are the problem, my opinion is they’re going to miss the electric revolution and all the spoils it will bring. About 20 years ago, I worked for a company that sold computer-aided design software. The product they sold was revolutionary. Honestly, the first time I saw it demonstrated, I got dizzy. I knew the world had changed for the better, much like how I feel about the arrival of the Volt. The CEO of that company, Brian presented an idea to his sales teams. He called it “The S Curve of Innovation.” He would draw on a whiteboard a curve. It started off almost horizontal, rising gradually as it moved from left to right, then its rise became quite steep before flattening out again at a much higher level than where it started.

The curve represents the opportunities companies have to capitalize on new technologies. In the beginning, at the left end of the curve, sales increases are slow, as many people don’t want to adopt a technology in its infancy or have a fear of change. The reddened part of the curve in the middle is the area where critical mass has been reached and sales begin skyrocketing. A company with a new technology at this stage will see sales and profits go up faster and faster. After a while, represented by the right end of the curve, the product and the market for it has matured and innovation in the product and sales increases level off. Of course, as the product ages and is replaced by newer technologies, there will be a gradual decline that increases in speed as the newer product is adopted until finally, the product disappears into the dustbin of history.

Just as this idea works for the companies, it also works for the those that get early exposure to the product and adopt it. Once the market in general understands and trusts the product and the reddish part of the curve starts rapidly going up, people who are experienced in the product, both in selling it and using it, can see their value (and remuneration) take the same kind of curve. This happened to me. Within three years of working for the company that sold the CAD system, I was recruited by another company to lead the pre-sales engineering team. My salary had doubled over that previous three years. Within another year, it had tripled compared to what it had been just four years earlier.

The reason I mention all this is that some of these dealers are making a mistake, but not all. Alaska may not be the best place to market a Volt. But if the dealers low sales numbers were caused by a lack of sales focus (which I have seen at many dealerships as I investigate EVs) they are going to miss a grand opportunity, both to participate in a revolution and in the windfall profits that will arise from it. I have to tell you, riding the curve is exciting and fun. I am grateful I got to experience a sea change in technology like that.

I’m sure the anti-Volt punditry will start later today although this is not indicative of poor sales at most dealerships.

The debate now, is where is the Volt in its curve right now? We’ll have a better idea today, when GM announces the December sales figures.

Yes, I will report on those numbers as soon as I see them published and will update my spreadsheet. (yay!)